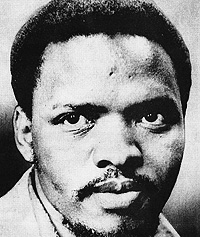

1946 - 12 September 1977

Article by Cyrille Hugon on his

death • Medical examination of Biko's death by Karla Jacobsen •

Why my hostname

is "biko" • Steve Biko

memorial page

A young black politician who died under brutal and degrading circumstances during the apartheid period. Biko's life reflected the lot of frustrated young black intellectuals. In his death he became a symbol of the martyrdom of black nationalists whose struggle focused critical world attention on South Africa more strongly than at any time since Sharpeville in 1960.

Biko was a black consciousness exponent who developed intellectually and emerged with others out of the changing literate African population in the major urban centres during the 1960s. Feeling deeply their subservience, they searched for self-identity and hoped to build up pride in a culture that was not emasculated by white state rule. Biko and his student colleagues had been receptive to the political ideas expressed by many black intellectuals and they learned to use the sheer emotional power of the message of black consciousness with bitter assertiveness. These ideas and slogans filtered down to a much broader group of socially unorganised people, angry and impatient for meaningful action, who made up a new African petty bourgeoisie.

Black university students had tried for many years to make progress through the multiracial National Union of South African Students (NUSAS) because it was outspoken in its criticism of government actions, especially at English-speaking universities where NUSAS membership was strong. Several young liberal white leaders of NUSAS were moved by the black cause and tried to protect politically active black students from government counter-action by speaking out for them. Media coverage of these dissident activities caused a dismayed response from the parents of white students who wished to shield their children from political involvement that could shatter their lives in detentions and banning orders. In a backlash of reaction white students disaffiliated themselves from NUSAS. This swing to the right left no channels for black students to express their anti-apartheid feelings. Dissatisfaction was intense. In the period 1967-68, one of the students who began to analyse and criticise the situation was Steve Biko, a medical student at Natal University. He was to become the hero of millions of Africans who rejected apartheid.

Biko, the son of a government clerk, was born in Kingwilliamstown. In 1963, when Poqo unrest in the eastern Cape was severe, Steve Biko had just entered Lovedale College when his brother was arrested and jailed on suspicion of outlawed Poqo activity. Steve was interrogated by the police and subsequently expelled. Thus began his resentment against white authority. In 1964 he went to Marianhill in Natal and attended a private Roman Catholic school, Saint Francis College. Though Christian principles had meaning for him, Biko, who was an articulate youth, resented whites influencing the thinking of the future of Africans.

At Wentworth, Natal University's medical school for blacks, he was elected to the Student's Representative Council (SRC), and in 1967 participated as a delegate to a NUSAS conference at Rhodes University. Here, black students were affronted when the host university prohibited mixed accommodation and eating facilities at the conference site. Reacting bitterly, he slated the artificial integration of student politics and rejected liberalism as empty gestures of people who really wished to retain the status quo. Black students were drawn to Biko in frank discussions about their predicament as second class citizens. At the University Christian Movement (UCM) meeting at Stutterheim in 1968 these usually reticent young people were enthusiastically supportive of Biko's idea for an exclusively all-black movement. In 1969, at the University of the North near Pietersburg, and with students of the University of Natal playing a leading role, African students launched a blacks-only student union, the South African Students' Organisation. SASO made clear its common allegiance to the philosophy of black consciousness. Biko was elected president.

Biko was scathingly critical of white liberals who 'could skillfully extract what suits them from the exclusive pool of white privileges'; and he was resentful that blacks were experiencing a situation from which they were unable to escape. The principles of liberty, equality, fraternity, rule of law, and civil liberties were incidental to those who were struggling for fundamental freedoms. Blacks had to 'go-it-alone'. The whole ideology of liberalism was questioned and rejected openly and emotionally by SASO with Biko as its main mouthpiece. With ever-growing radicalism he explained why he was against integration: 'I am against the fact that a settler minority should impose an entire system of values on an indigenous people.' (S. Biko. [Frank Talk] 'Black Souls in White Skins' in Gerhart, 1970: 263, 266)

South Africa's complex society of blacks accepted these negative ideas with mixed reactions. Shocked white liberals, with their sincerity and deep convictions in question, felt they had become easy scapegoats for another racist organisation. The idea that blacks might determine their own destiny, the movement's pride in black consciousness, and a new Africanism swept black campuses, strongly influencing those who had experienced the frustrations of the system of Bantu Education, of continual deference and feelings of inferiority to whites. In a short time SASO became identified with 'Black Power' and African humanism and reinforced by ideas emanating from black America and Africa.

In particular, Biko preached to moderate blacks that racial polarisation of society into hostile camps was a preliminary to race conflict and a strategy for change. He was convinced that, if blacks were not to sink into apathetic acceptance of the system of separate development, continuous agitation had to take place to shake them up.

In 1971, to shake up adults and promote their bold objectives, SASO leaders tried to establish an adult wing of their organisation. At the 1972 SASO conference hostility towards black leaders operating from officially approved institutions of separate development was made manifest when the outgoing president of SASO, Temba Sono, was ousted because he recommended some form of co-operation with selected leaders within the apartheid system. Biko described Sono's speech as 'very dangerous' (Black Review, 1972:25). In fact, Sono had Chief Gatsha Buthelezi in mind when he pleaded for some sort of co-operation with selected leaders, saying he was a 'force you cannot ignore' (Horrell, 1972:30).

But Biko saw all moderates working within the system as 'collaborators' and, with the expulsion of Sono, the radical ideology was entrenched. They faced many difficulties in this period before the 1976 Soweto Riots when youth erupted in the lead. Not least was the ingrained African custom of youth being required to defer to age. Dismayed parents, who had sacrificed much for the education of their children, were reluctant to see their schooling disrupted. More cautious older political leaders feared such open militancy would get their children nowhere.

For security reasons Biko and the young leaders stressed the psychological dimensions of culture and identity, but they never lost sight of their revolutionary political objectives as they endeavoured to turn a student activity into a participating national organisation backed by financial resources and much needed mobility. An adult wing called the Black Peoples Convention was eventually launched in 1972. Almost immediately it clashed with the police. Eight black consciousness leaders were banned in 1973 and publication of BPC material became difficult. But by the end of the year forty-one branches were said to exist, black churchmen were becoming increasingly politicised and black consciousness speakers highly courageous and more provocative in their outspokenness and defiance of white authority. Growing politicisation of the high schools resulted in mounting expulsions and stinging attacks on black education. Boycotts and school closures followed as developing black-white confrontation began to bring about the sought after racial polarization needed to bring about change. At the black schools Biko and his student leaders became heroes and high school youth organisations became the nurseries for revolt.

The government reacted by systematically depriving SASO of its leaders. In 1973 a flurry of banning orders were issued: Biko, Pityana and other SASO and BPC leaders were detained under the Terrorism Act and the following year nine leaders of SASO and BPC were charged for fomenting disorder. The accused used the seventeen-month trial as a platform to state the case of black consciousness. They were found guilty and sentenced to various terms of imprisonment, but were acquitted of being party to a revolutionary conspiracy. Their convictions simply strengthened the black consciousness movement for the repression under the Terrorism Act caused blacks to lose sympathy with moderate evolutionary policies, creating more militancy and hope for emancipation. In June 1976 high school students and police clashed violently and fatally, and continuing widespread urban unrest threatened law and order.

In the wake of the urban revolt of 1976 and with the prospects of national revolution becoming increasingly real, security police detained Biko, the outspoken student leader, on August 18th. He was thirty years old and said to have been extremely fit when arrested. He was taken to Port Elizabeth and on 11 September 1977 he was moved to Pretoria, Transvaal. On 12 September, he died in detention - the 20th person to have died in detention in the preceding eighteen months. A post-mortem was done the day after Biko died, at which the family were present, but skepticism was widespread about the explanation by Minister of Justice and Police Jimmy Kruger that Biko died while on a hunger strike. Medical reports received by Minister Kruger were not made public.

Three South African newspapers carried reports that Biko did not die as a result of a hunger strike. One of these papers, The World, was banned. Minister of Justice Kruger took the Rand Daily Mail to the South African Press Council after it had published a front page story claiming that Steve Biko had suffered extensive brain damage. Furthermore, the Johannesburg Sunday Express said that sources connected with the forensic investigation maintained that brain damage had been the cause of death. In Britain it was understood from South African sources that fluid drawn from the spine revealed many red cells - an indication of brain damage.

Twelve western countries sent envoys to his funeral. A photograph of Biko lying in his coffin was taken secretly just before the funeral and sent by an underground South African source to Britain and seen as added proof that the leader had been beaten to death while in prison.

These disclosures were very damaging to South Africa, caused an international outcry and condemnation of South Africa's security laws, and led directly to the West's decision to support the UN Security Council vote to ban mandatory arms sales to South Africa (Resolution 418 of 4 November 1977). Biko's brutal death made him a martyr in the history of black resistance to white hegemony, inflamed huge black anger and inspired a rededication to the struggle for freedom. Progressive Federal Party parliamentarian Helen Suzman warned Minister of Justice Jimmy Kruger that 'the world was not going to forget the Biko affair', and she said, 'We will not forget it either.' Kruger's reply that Biko's death 'left him cold' echoed around the world.

A widespread crackdown of black student organizations and political movements followed, and in October, just before the inquest, police swooped on seventeen Black Consciousness resistance organizations. Two of Biko's white friends, the Reverend Beyers Naudé and Donald Woods were banned, and Percy Qoboza, editor of the World, was banned for allegedly writing inflammatory articles about the manner of Biko's death. Prime Minister Vorster called a snap election and a large majority of white voters united in a call for Vorster's Nationalist Government to remain in power to face the formidable challenge of a distinctly polarized black population.

Prior to this, at the inquests of a number of detainees who died under suspicious circumstances magistrates declined to examine the interrogation methods used and attributed death to natural causes, suicides or prison accidents. At the inquest into Biko's death no government official was prepared to condemn the treatment meted out to Biko. The circumstances of his death were said to be inconclusive and death was attributed to a prison accident. Yet, evidence led during the 15-day inquest into Biko's death revealed otherwise. During his detention in a Port Elizabeth police cell he had been chained to a grill at night and left to lie in urine-soaked blankets. He had been stripped naked and kept in leg-irons for 48 hours in his cell. A blow in a scuffle with security police led to him suffering brain damage by the time he was driven naked and manacled in the back of a police van to Pretoria, where, on 12 September 1977, he died.

Two years later a South African Medical and Dental Council (SAMDC) disciplinary committee found there was no prima facie case against the two doctors who had treated Biko shortly before his death. Dissatisfied doctors, seeking another inquiry into the role of the medical authorities who had treated Biko shortly before his death, presented a petition to the SAMDC in February 1982, but this was rejected on the grounds that no new evidence had come to light.

It took eight years and intense pressure before the South African Medical Council took disciplinary action. On 30 January 1985 the Pretoria Supreme Court ordered the SAMDC to hold an inquiry into the conduct of the two doctors who treated Steve Biko during the five days before he died. Judge President of the Transvaal Mr Justice W G Boshoff said in judgment handed down that there was prima facie evidence of improper or disgraceful conduct on the part of the `Biko' doctors in a professional respect.

Biko's death did not put an end to ill treatment, however. Years later, when young Dr Wendy Orr made her disclosures about the treatment of detainees in the eastern Cape it became clear that conditions had changed very little. In September 1987 Helen Suzman once again produced claims of torture and ill treatment in detention with thirty-seven signed affidavits.

Bibliography

Biko, S., [Frank Talk], 'Lets Talk

About Bantustans,' SASO Newsletter, September-October 1972, pp.

18-21

Davenport, T.R.H., South Africa, a Modern History. 2nd Edition

(1977)

Gerhart, G.M., Black Power in South Africa (1979)

Hellman, E.

and Lever, H., (Eds.) Conflict and Progress (1979)

Lodge, T., Black

Politics in South Africa since 1945 (1983)

Random, P. (ed), Survey of

Race Relations in South Africa (1982)

Cooper, C. et al., Survey of Race

Relations in South Africa (1983)

Horrell, M. et al. Survey of Race

Relations in South Africa (1972)

Sono, T., `In search of a Free and New

Society.' Minutes of the Proceedings of the 3rd General Students' Council

of the South African Students Organisation, St Peter's Seminary,

Hammanskraal, 2-9 July 1972, pp. 5,7

SASO Newsletter, September-October

1972, pp. 13-14 [SASO files]

Rand Daily Mail, 11 November,

1972.

click here to read an article by Cyrille Hugon on his

death

click here to see a medical examination of Biko's death by

Karla Jacobsen

link to webpage entitled: Why my hostname is "biko"

Steve Biko memorial page with several related

links