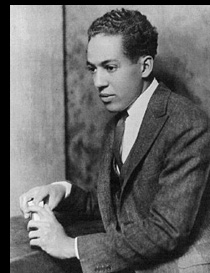

Langston Hughes

Writer, editor, lecturer

By Donna Akiba Sullivan Harper

|

Langston Hughes |

|

Writer, editor, lecturer |

|

|

By Donna Akiba Sullivan Harper |

|

Langston Hughes achieved fame as a poet during the burgeoning of the arts known as the Harlem Renaissance, but those who label him "a Harlem Renaissance poet" have restricted his fame to only one genre and decade. In addition to his work as a poet, Hughes was a novelist, columnist, playwright, and essayist, and though he is most closely associated with Harlem, his world travels influenced his writing in a profound way. Langston Hughes followed the example of Paul Laurence Dunbar, one of his early poetic influences, to become the second African American to earn a living as a writer. His long and distinguished career produced volumes of diverse genres and inspired the work of countless other African American writers.

Although his youth was marked with transition, Hughes extracted meaning from the places and people whence he came. The search for employment led his mother and step-father, Homer Clark, to move several times. Hughes moved often between the households of his grandmother, his mother, and other surrogate parents. One of his essays claims that he has slept in "Ten Thousand Beds." Growing up in the Midwest (Lawrence, Kansas; Topeka, Kansas; Lincoln, Illinois; Cleveland, Ohio), young Hughes learned the blues and spirituals. He would subsequently weave these musical elements into his own poetry and fiction.

In a Cleveland, Ohio, high school, Hughes was designated "class poet" and there he published his first short stories. He became friends with some white classmates, yet he also suffered racial insult at the hands of other whites. He learned first-hand to distinguish "decent" from "reactionary" white folks, distinctions he would reiterate in his book Not Without Laughter and in his "Here to Yonder" columns in The Chicago Defender. Seeking some consolation and continuity in the midst of the myriad relocations of his youth, he grew to love books. His love of reading developed into a desire to write as he sought to replicate the powerful impact other writers from many cultures had made upon him. In his writing, Hughes accomplished an important feat. While others wallowed in self-revelation as a balm for their loneliness, Hughes often transformed his own agonies into the sufferings endured by the collective race and sometimes all of humankind.

After graduating from Central High School in Cleveland in 1920, he moved to Mexico City to live with his father for one year. His mother fumed about his departure, and his father offered him little warmth. Yet, with his unique gift for writing, Hughes turned the pain engendered by his parents' conflict into the noted poem, "The Negro Speaks of Rivers," published by Crisis in 1921.

Hughes gathered new impressions and new insights about race, class, and ethnicity in Mexico, where his ability to speak Spanish and his appearance often allowed him to blend in. Even Americans who would not have spoken to him in Cleveland or Kansas City would converse with him as a "Mexican" on the train. Although brown skin no longer remained an obstacle in Mexico, Hughes saw that poverty still reached many Mexicans. Numerous works, including a children's play, capture fragments of Hughes's days in Mexico.

When he left his ambitious father in Mexico, Hughes was expected to earn an engineering degree at Columbia University. Breaking abruptly with his insulted father, in the first of many brave and daring moves, Hughes withdrew from Columbia in 1922, and one year later he began his world travels. He visited several ports in Africa and he worked as a dishwasher in a Paris cabaret. Poems and short stories capture some of his impressions abroad. He sent a few of the pieces back home, where they were published, enhancing his growing reputation as a writer.

When financial strain ended his travels, Hughes returned to the United States. He once again attempted various forms of work, this time in Washington, D.C., where his mother had moved. Besides blue-collar work, he also served briefly in the office of publisher and historian Carter G. Woodson. Although he respected Dr. Woodson's significance to the African American community, Hughes did not like the eye-strain or the detail of his assignments. Nevertheless, he continued to write. In 1925 he won first prize in poetry in Opportunity magazine. He also met writer Carl Van Vechten, who assisted Hughes in securing a book contract with publisher Alfred A. Knopf. Hughes also enjoyed his "discovery" by poet Vachel Lindsay as the "busboy poet."

Hughes's first volume of poetry, The Weary Blues, appeared in 1926. That same year, Hughes returned to college, this time as an older student and an acclaimed poet at the nation's first African American college, Lincoln University, in Pennsylvania. Spending any available weekend soaking up theater and music in nearby New York City, Hughes satisfied academic requirements during the week. A second volume of poetry, Fine Clothes to the Jew, was published in 1927. The Harlem Renaissance was in full bloom, and Hughes became one of the celebrated young talents who flourished during this era. Some controversy attended his celebrity, however. Not all blacks relished his use of dialect, his interpretation of blues and jazz, or his vivid and sensitive portrayals of workers. Hughes faced harsh criticism, including his designation not as poet laureate but as the "poet low-rate" of Harlem.

As Hughes completed his years at Lincoln University in 1929, he also completed his first novel, Not Without Laughter, published in 1930. Still receiving financial assistance from Charlotte Mason, the patron he shared with Zora Neale Hurston and Alain Locke, among others, Hughes also accepted her advice regarding the contents and tone of the novel. He expressed disappointment with the completed novel, but the text remains in print, retaining uplifting representations of the diverse populations within the black community.

In 1930, however, Hughes separated from the control and the financial support of Mason. His integrity meant more to him than any luxuries her wealth could provide, thus, as with the break from his father, Hughes abandoned financial security in search of his own goals. When Mason disapproved of him, Hurston and Locke, who remained loyal to her, dropped from Hughes's list of associates.

Following the advice of Mary McLeod Bethune and sponsored by an award from the Rosenwald Foundation, Hughes began to tour the South with his poetry. Highly regarded as a reader, handsome and warm in person, Hughes gained many readers and admirers during his tours. He also visited the Scottsboro Boys in Alabama, who were accused of raping a white woman. Hughes created poetic and dramatic responses to the men's plight and the mixed reactions of the American public.

In 1932, Hughes went to Russia with a group of African Americans to assist with a film project that never bore fruit. When the project dissolved, most of the participants returned to the United States, but Hughes set off to explore the Soviet Union. In his own observations of the Soviet Union, Hughes saw many reasons to appreciate communism. Thus, while many other American writers were attracted to socialistic perspectives during the depression years, Hughes openly praised practices he had observed in the Soviet Union: no "Jim Crow," no anti-semitism, and education and medical care for everyone. He wrote numerous poems to capture those travels, and later, in both his Chicago Defender column and in his second autobiography, I Wonder As I Wander (1956), he recorded impressions of his travels. Following the journey to the Soviet Union, Hughes completed work on his first volume of short stories, The Ways of White Folks (1934). In 1936 he received a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship and worked with the Karamu House in Cleveland, Ohio, on several plays. His interest in theater continued in New York, where he founded the Harlem Suitcase Theater in 1938. A 1941 Rosenwald Fund fellowship further supported his play writing. However, he also moved into another genre. His interesting family heritage, his remarkable travels, and his participation in African American culture led to his first autobiographical volume, The Big Sea (1940).

When the United States plunged into World War II, Hughes escaped military service, but he put his pen to work on behalf of political involvement and nationalism. Writing jingles to encourage the purchase of war bonds, and writing weekly columns in The Chicago Defender, Hughes encouraged readers to support the Allies. His appeals remained consistent with the "Double-V" campaign upheld by the black press: victory at home and victory abroad. Hughes encouraged black Americans to support the United States in its goals abroad, but he encouraged the government to provide for its own citizens at home the same freedoms being advocated abroad. A fictional voice emerged from these columns, that of Jesse B. Semple, better known as "Simple." While the character initially appeared as a Harlem everyman who needed encouragement to support the racially segregated U.S. armed forces, Simple evolved into a popular and enduring fictional character. The first volume of stories to develop from Simple's appearances in the Chicago Defender was published by Simon and Schuster in 1950, Simple Speaks His Mind.

Hughes retained his interest in theater, working with Kurt Weill and Elmer Rice to develop a musical adaptation of Rice's play Street Scene. The musical opened on Broadway in 1947, where it enjoyed a brief run that proved financially beneficial to Hughes.

Another significant theatrical collaboration involved William Grant Still, the first black composer in the United States to have a symphony performed by a major symphony orchestra, the first to have an opera produced by a major company in America, and the first to conduct a white major symphony orchestra in the Deep South. They collaborated on Troubled Island, based on the life of Jean Jacques Dessalines of Haiti, which Hughes had transformed from a play to a libretto. Hughes was in Spain reporting on the Spanish Civil War for the Baltimore Afro-American while Still adapted his libretto for an opera. Yet the project finally reached completion and opened in New York in 1949.

During the 1940s Hughes's poetry also continued to be published: Shakespeare in Harlem (1942), Fields of Wonder (1947), and One-Way Ticket (1949). He also engaged in some translation projects involving both French and Spanish texts. Hughes's success as a writer were acknowledged through the award of $1,000 from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1945. With his friend Arna Bontemps, he edited The Poetry of the Negro (1949).

The 1950s brought the Cold War and the horrors of Senator Joseph McCarthy's subcommittee on subversive activities. With his published record of socialistic sentiments and his public associations with known Communists, Hughes endured several years of attacks and boycotts. In 1953 he received a subpoena to testify about his interests in communism. Holding fast to his own dream of sustaining his career as a writer, Hughes salvaged his image as a loyal American citizen by insisting that the pro-Communist works he had published no longer represented his thinking. Although he bravely challenged authority figures earlier in his life, in this situation he acted to protect his chosen profession. He retained speaking engagements and his works continued to sell, but he lost the respect of some political activists. Communists bitterly resented the way he abandoned professed members of the party, including W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson, whom Hughes had lauded in earlier decades. Hughes chose self-preservation and sustained his career as a writer.

A career as a writer often led Hughes to accept multiple book contracts simultaneously, thereby imposing upon himself an arduous schedule of production. Correspondence housed in the Beinecke collection at Yale University, in the Special Collections of Fisk University, in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and collected in the Charles Nichols edition of Arna Bontemps-Langston Hughes Letters, 1925-1967 (1980) reveal Hughes's frantic pace of writing, editing, revising, and publishing from the 1950s to the end of his life. He began to offer juvenile histories, including Famous American Negroes and The First Book of Rhythms in 1954, and The First Book of Jazz and Famous Negro Music Makers in 1955. He collaborated with photographer Roy De Carava on The Sweet Flypaper of Life in 1956, and in the same year he wrote Tambourines to Glory, The First Book of the West Indies, and his second autobiography I Wonder As I Wander.

Hughes's character Jesse B. Semple continued to thrive, appearing frequently in his weekly column in the Chicago Defender. A second book, Simple Takes a Wife (1953) and a third, Simple Stakes a Claim (1957), led to a musical version, Simply Heavenly, which ran on Broadway in 1957.

The last ten years of Hughes's life were marked by an astonishing proliferation of books: juvenile histories, poetry volumes, single genres anthologies (Laughing to Keep From Crying [short stories], 1952; Selected Poems, 1957; The Best of Simple, 1961; and Something in Common and Other Stories, 1963); a collection of genres (Langston Hughes Reader, 1958); and an adult history of the NAACP (Fight for Freedom, 1962). Hughes edited An African Treasury (1960); Poems from Black Africa, Ethiopia, and Other Countries (1963); New Negro Poets: U.S.A. (1964); and The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers (1967), in which he became the first to publish a short story by Alice Walker. Some of his efforts in drama were collected by Webster Smalley: Five Plays by Langston Hughes: Tambourines to Glory, Soul Gone Home, Little Ham, Mulatto, Simply Heavenly.

Hughes was inducted into the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1961, the year he published his innovative book of poems to be read with jazz accompaniment, Ask Your Mama: 12 Moods for Jazz. During the 1950s he also recorded an album of himself reading some of his earlier verse, accompanied by jazz great Charles Mingus.

Hughes shifted his weekly newspaper column from The Chicago Defender to The New York Post. While Hughes had never shunned aggressive politics, he was mistaken for a timid accomodationist. Readers' letters revealed ignorance about his consistently positive appreciation of black people and culture and his consistently fair treatment of people of all races and cultures. Resilient even to the end of his life, Hughes withstood accusations that he foolishly joked about racial turmoil. He endured the hostile criticism, but in 1965 he ended his 22-year tenure as a newspaper columnist.

Hughes's death on May 22, 1967, apparently resulted from infection following prostate surgery and two weeks of treatment at the New York Polyclinic Hospital. Memorial services followed many of his own wishes, including the playing of Duke Ellington's "Do Nothing Till You Hear from Me."

The works of Hughes continued to appear even after his death. He had prepared The Panther and the Lash (1967), a collection of poems, but it was not published until after his death. Collaborations such as Black Magic (with Milton Meltzer, 1967) and a revision of the 1949 anthology, The Poetry of the Negro 1746-1970 (edited by Hughes and Arna Bontemps, 1970) were published, acknowledging his contributions and lamenting his death. Subsequent years have brought Good Morning Revolution, a collection of radical verse and essays (edited by Faith Berry, 1973); Collected Poems, a comprehensive and well-indexed chronological collection of his poetry (edited by Arnold Rampersad and David Roessel, 1994); The Return of Simple, a new collection of his Jesse B. Semple tales (edited by Akiba Sullivan Harper, 1994); Langston Hughes and the Chicago Defender, a collection of his non-Simple newspaper columns (edited by Christopher C. De Santis, 1995); and Langston Hughes Short Stories, retrieving previously unpublished short stories and collecting some now out of print (edited by Akiba Sullivan Harper, 1996).

Through his writing and through his generosity as a "dean" of literature, Hughes nurtured scores of writers and left behind an enduring legacy of literature. More than 20 years after his death, on the eighty-ninth anniversary of Hughes's birth in 1991, amid great celebration by noted writers such as Maya Angelou and Amiri Baraka, his cremated remains were interred beneath the commemoratively designed "I've Known Rivers" tile floor in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem. Visitors to this noted research center may see this floor, pay respects to his remains, and remember the man.