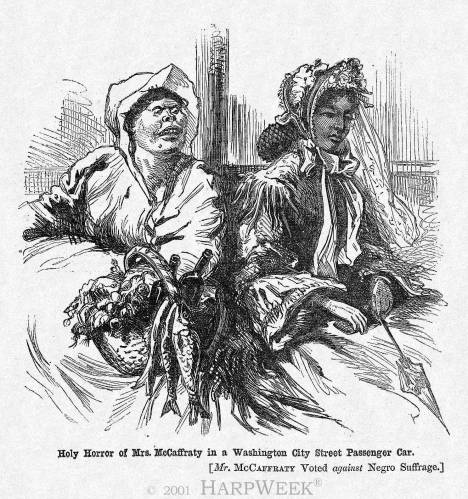

"Holy Horror of Mrs. McCaffraty in a Washington City Street Passenger Car."

On February 24, 1866, Harper's Weekly featured a cartoon about voting rights for African Americans.

Published After Southern States' Response To Reconstruction Act

|

"Holy Horror of Mrs. McCaffraty in a Washington City Street Passenger Car." |

|

On February 24, 1866, Harper's Weekly featured a cartoon about voting rights for African Americans. |

|

|

Published After Southern States' Response To Reconstruction Act |

|

This Harper's Weekly cartoon by an unknown artist depicts the racial prejudice that underlay the rejection of black manhood suffrage in Washington, D. C. During the summer of 1865, while Congress was in recess, President Andrew Johnson implemented his Reconstruction plan for the former Confederate states, all of which quickly complied with its lenient requirements. When Congress reconvened in December 1865, it refused to recognized the reconstructed state governments or to seat their congressional representatives. Republicans were disturbed by the reluctance of white Southerners to ratify the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, their refusal to grant voting rights to black men, their enactment of black codes limiting the rights and liberties of blacks, and their election of former Confederates, such as Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens, to state and national offices.

Radical Republicans believed that voting rights for black men, who could not vote in most Northern states as well as in Southern ones, was the linchpin for safeguarding other rights. In 1865, Republicans proposed popular referenda for black manhood suffrage in the states of Connecticut, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, and the territory of Colorado, but all were defeated by the electorate. Nationally, radical Republicans sought a precedent for federal authority over voting rights by endeavoring to enact black manhood suffrage for the District of Columbia.

To dissuade congressional action, suffrage opponents organized a popular referendum among the city's white voters in December 1865. Nearly 7,000 ballots were cast against black voting rights, with only 35 in favor.

In this cartoon, the black woman on the right is depicted as a lady of beauty, refinement, and wealth (or at least middle-class respectability). On the left, the Irish-American woman (safely assumed to be Catholic) is stereotyped with ape-like features and working-class attire. A servant or housewife, Mrs. McCaffraty has been to the market to purchase fresh produce and fish. Her basket also holds two bottles of alcohol, frequently associated with Irish-Catholics. The bracketed remark lets viewers know that she represents the type of disreputable person who opposes black manhood suffrage. Images of Catholic Irish-Americans were stereotyped consistently in the pages of Harper's Weekly over the decades of the late-nineteenth century.

The images of blacks in Harper's Weekly would go through several phases over the decades. From 1857, when the newspaper began publication, until the Civil War, pictures of blacks were limited in number, but often stereotyped when they did appear. After 1863, when George William Curtis became editor and Thomas Nast began contributing cartoons regularly, African Americans were usually drawn with dignity and respect. The 1870s were a period of transition, as it was for the country itself. From the late 1870s, with the end of Reconstruction, through the turn of the century, images of blacks were exaggerated into increasingly severe racial stereotypes. This 1866 cartoon appears during the era when African Americans were most visibly supported by the journal.

In January 1866, the U.S. House passed a bill enfranchising black men in the District of Columbia, but the measure failed in the Senate. In March 1867, Congress enacted, over President Johnson's veto, the first Reconstruction Act, which required among its stipulations that the former Confederate states grant voting rights to black men. In March 1870, the 15th Amendment was ratified which declared that voting rights cannot be denied on the basis of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It brought Northern states in line with Southern ones. With the end of Reconstruction, though, voting rights for blacks (especially in the South) were usually not enforced until the "Second Reconstruction" of the mid-twentieth century.

--Robert C. Kennedy--